By Mike Hobbiss

Unsurprisingly, teachers are very interested in the brain, and excited about the potential for psychology and neuroscience evidence to be used in improving what they do (see for example the responses to this survey). It’s a shame, then, that so little time in many teacher training routes has traditionally been given over to psychology and the science of learning. Especially if you trained five or more years ago (as I did), it seems to have been very rare to have received more than a cursory introduction to the subject… apart from one notable exception. However little psychology gets covered otherwise, one mandatory inclusion on many teacher training courses is constructivism — the idea that every individual constructs their own understanding and knowledge of the world, based on their own unique experiences. As a result, constructivist ideas are undoubtedly the most widely held ‘folk-psychological’ belief about learning amongst current teachers (See Torff, 1999, and Partick & Pintrich, 2001 for more on the content of teacher training and changes in trainee teachers’ beliefs about learning).

In this post I am going to argue that this state of affairs is dangerous. Importantly, though, the problem is not that constructivism is wrong. Constructivism works well as a theory of learning. The problem comes, however, when it is assumed that the theory of learning implies a particular pedagogical approach (‘educational constructivism’, or sometimes the closely related approach of ‘constructionism‘). Using evidence from neuroscience, I will try to show that there is a great deal of support for constructivism the learning theory, and a good deal less for constructivism the pedagogical approach. I’ll use the evidence underpinning the theory of ‘Neuroconstructivism’ (Mareschal et al., 2007), one of the most popular theories of developmental cognitive neuroscience, to help me with this.

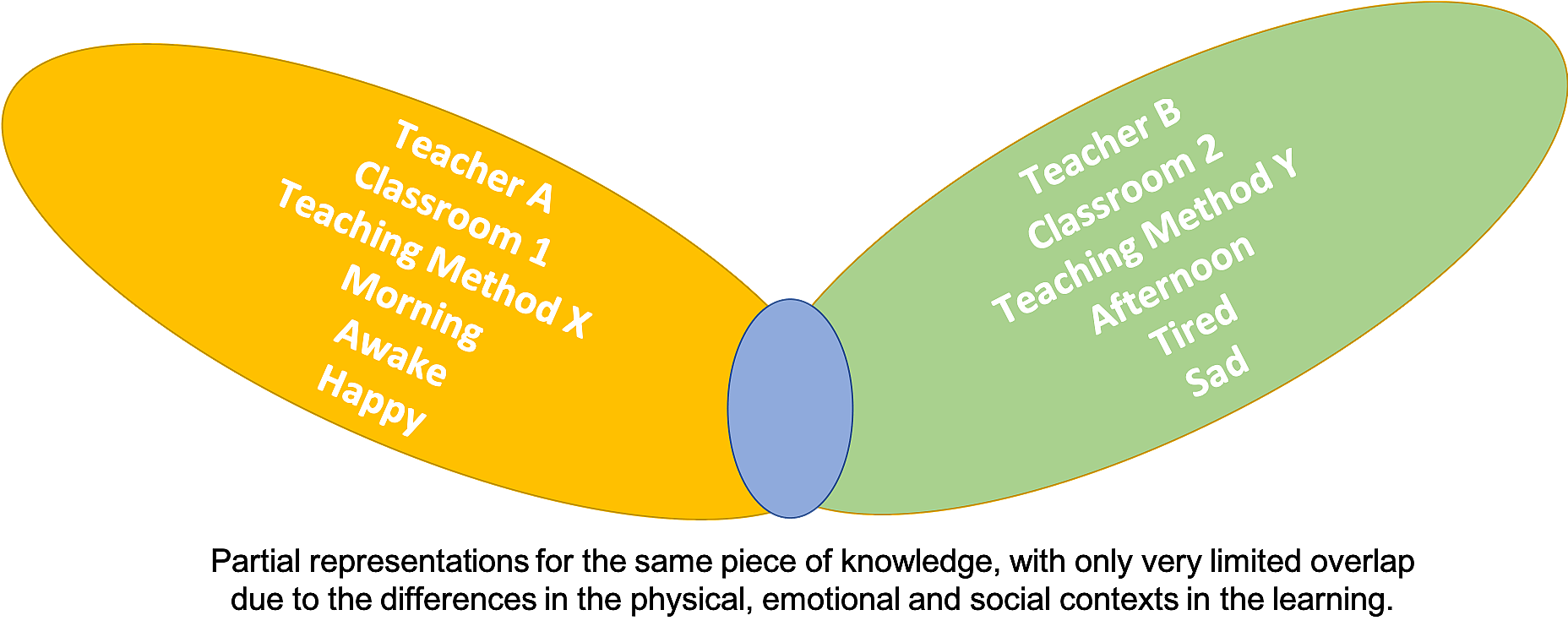

Partial representations, and context-specificity

A central feature of neuroconstructivism is that the development of our brains and the storage of information in them is hugely context-dependent. At any one moment, activity in the brain is a reflection of the context that the organism finds itself in. Mareschal et al., provide four different levels where the activity of the brain is constrained by the context in which it occurs: neural, network, bodily and social. I looked in more detail at these four levels in a previous description of the theory. The important point, though, is that brain activity reflects the precise state of the organism at the time of the event, so any new piece of ‘learning’ will be encoded completely within the context of the learning experience, rather than reflecting any general underlying feature of it. In the terminology of the theory, we are only ever able to create ‘partial representations’; representations of the world which capture some, but not all of it. Partial representations are, by their very nature, completely context-dependent; that is, they reflect the features of the world (and of the brain) which were the case when the information was originally stored.

More on: